Will Sheffield Wednesday Provide Championship Club Spending Wake-up Call?

Christopher Winn, Programme Leader for MSc Football Business at UCFB discusses the truths and consequences of Sheffield Wednesday’s punishment by the EFL for beaches of financial rules and whether it will provide a wake-up call for Championship clubs’ spending habits?

It’s no secret that the Championship is a hotly contested battleground, populated by both a host of former Premier League teams and ambitious pretenders to a place in the lucrative top tier of English football.

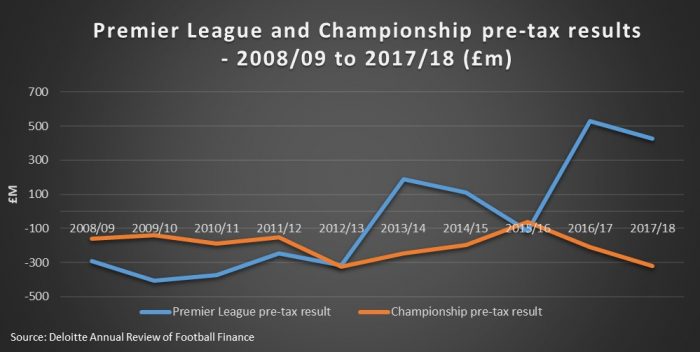

However, despite the correlation between wage spend and success in the division being extremely low – demonstrating a level of competitive balance evident to us all on a weekly basis – most clubs still attempt to gain an advantage through wage expenditure, outspending revenues and reporting unsustainable losses. Between 2013/14 and 2017/18 alone, Championship clubs collectively generated pre-tax losses in excess of £1 billion.

It is this type of unsustainable financial behaviour that led UEFA to introduce the concept of Financial Fair Play at the start of the 2011/12 season, encouraging clubs to operate on the basis of their own revenues, and protecting the long term viability of the game.

Domestic versions of these rules – now referred to as Profitability and Sustainability Regulations – have since been adopted by both the Premier League and the Championship, with the Premier League also operating their own wage specific Short Term Cost Control Measures.

But while the Premier League, in part aided by significant increases in broadcast revenue receipts, has seen improved financial health since the advent of the regulations, the same cannot be said of the Championship, with even the apparent improvement in profitability in 2015/16 underwritten by over £200m of loan write-offs to P&Ls by four clubs in that season (Source: Deloitte).

The Championship rules themselves allow clubs to generate pre-tax losses of up to £13m per season over a rolling three-year period, with exclusions allowed for depreciation, amortisation of non-player intangibles, and expenditure related to women’s football, youth development and community development. This figure increases to £35m per season for any of those three seasons spent in the Premier League. The EFL also has the power to revalue any transactions not carried out at arms’ length (i.e. fair market value) in the course of the calculation.

Championship clubs breaching these collective levels will then be subject to the EFL Disciplinary Committee’s range of powers, including fines, points deductions, embargoes, even League expulsion.

Crucially, these regulations do not directly regulate wage expenditure, with clubs exploring increasingly creative loopholes to bring their pre-tax results back to acceptable positions without reducing wage expenditure.

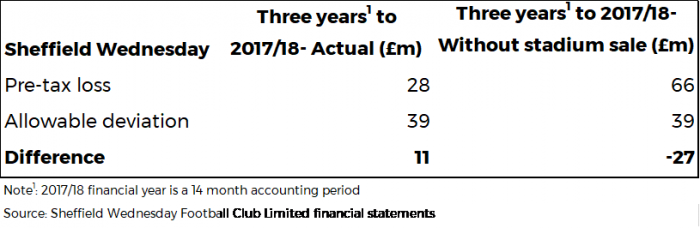

In the 2017/18 season, Sheffield Wednesday sold their stadia to their owners for around £61m, generating a profit on disposal of £38m to set against respective losses. While some clubs use of this technique in 2017/18 has passed the EFL’s scrutiny, Sheffield Wednesday have been formally charged by the EFL with respect to ‘how and when the stadium was sold and the inclusion of the profits in the 2017/18 accounts.’

Given the quantum of the club’s allowable expenses under the rules are negligible, the argument as to whether the stadium sale has been posted in the correct accounting period will very much make or break the club’s compliance with the Profitability and Sustainability Regulations.

The only club to be penalised under the existing regulations so far is Birmingham City, who were deducted nine points by the EFL in March 2019 after collective losses of almost £59m in the three seasons to 2017/18. However, no attempt was made to use an accounting loophole to reduce losses in their case.

There are examples of clubs breaching the previous incarnation of the regulations in their promotion campaigns, however these came at a time when the regulations covered just 12 month periods and stipulated a sliding scale of financial fines for clubs breaching the rules while gaining promotion.

Most notably QPR attempted to write off a shareholder loan of £60m in 2013/14 to turn a £70m loss into a £10m loss. The club recently agreed a settlement with the EFL of a total fine of £42m after several years of legal challenge.

All these clubs have one thing in common though- that being extremely high, unsustainable wage/revenue ratios:

– Sheffield Wednesday were running at 168% in 2017/18;

– Derby County, who also sold their stadium to their owner to generate a £40m profit on disposal, were running at 162% in 2017/18;

– Birmingham City were running at 194% in 2017/18, and

– In 2013/14, QPR had a wage/revenue ratio of 195%.

Given the EFL recently appeared to set an example when dealing with QPR’s attempt to offset their losses, the case of Sheffield Wednesday could be another watershed moment in the ongoing attempts to see Championship clubs operate within their means.

But given all these truths come as a consequence of unsustainable wage expenditure, maybe it is time for the clubs themselves to agree and vote on a refined or additional set of rules that directly regulate the amounts they are able to spend on wages, and in doing so safeguard their future viability.